Bill for an Act on the Confirmation of Private Plans , the Dutch Scheme

Introducing the possibility to impose a compulsory plan on shareholders and creditors of struggling businesses will make the Netherlands attractive for restructuring

P.C. van Prooijen RV & Martin A. Poelman[1]

Summary

The bill for an Act on the Confirmation of Private Plans (‘ACPP’), submitted on 5 July 2019, enables a business on the brink of insolvency to impose a compulsory plan on its creditors and shareholders, outside suspension of payments and bankruptcy proceedings. The ACPP bill takes inspiration from the British Scheme of Arrangement and the US Chapter 11 procedure. The pre-insolvency plan provided for in the bill will give companies in financial difficulties an excellent opportunity to restructure. It will then no longer be necessary, as Van Gansewinkel Groep BV did in 2015, for example, to move to England for this purpose. The Netherlands is expected to become a very appealing jurisdiction for struggling businesses wishing to restructure.

In this October 2019 contribution, the authors discuss the main features of the ACPP bill and will discuss certain topics in more detail in several follow-up articles.

Introduction – ACPP

The bill for an Act on the Confirmation of Private Plans (ACPP) is part of the Bankruptcy Law Review Programme. On 5 July 2019, the government submitted the bill, including the explanatory memorandum, to the Lower House of the Dutch Parliament. The bill introduces a scheme to create a compulsory plan outside bankruptcy. The bill, which will be included in the Bankruptcy Act, facilitates the early restructuring of problematic debts based on a plan between the business and its creditors and shareholders.[2] The plan can amend the rights of all categories of creditors and shareholders.[3] The Court can ratify (confirm) this plan. Unlike in suspension of payments and bankruptcy proceedings, the rights of not only unsecured creditors but also of preferential creditors may be amended by the plan.

Besides amending the rights of creditors, the plan can also amend the rights of shareholders. According to the Explanatory Memorandum, a plan involving a debt for equity swap should be given particular consideration in this context. After all, this would dilute existing shareholders’ rights. The ACPP will also make it possible to unilaterally terminate existing agreements if the other party does not agree to a proposed voluntary amendment or termination.

According to the Explanatory Memorandum, the ACPP should be seen as a last resort. The ACPP does not aim to undermine the existing practice of out-of-court restructuring, but rather to reinforce it. Because the ACPP offers an effective way of having a court-imposed solution, dissenters will be less able to be over-demanding. This will facilitate reaching consensus (Explanatory Memorandum no. 1). Moreover, the ACPP has been designed as far as possible as a framework arrangement, to give the parties more flexibility to agree on a plan tailored to the specific circumstances of the case (Explanatory Memorandum 3.1).

Besides legal aspects, economic and financial issues also play a role in the ACPP: questions relating to the assessment of a business’s viability; the profitability of its operational activities; how much new money is needed to continue its activities; the extent of the damage resulting from terminating reciprocal agreements; the financial, legal, and operational information to be provided to the parties concerned; the expected return of the various classes in the reconfigured capital structure; and the form this reconfigured capital structure will take. In addition, two values of the business in question play an important role: the value in a liquidation scenario (liquidation value) and the value in a reorganization scenario (reorganization or going concern value).

What is the reason?

A business faced with serious financial problems often seeks a solution in:

(a) an out-of-court plan with creditors (deferred payment or partial discharge of debt, or the conversion of debt into share capital), or, whether or not in combination with (a), in:

(b) raising new capital.

As rightly noted in the Explanatory Memorandum, current law requires the cooperation of creditors (scenario a) and shareholders (scenario b)[4]. Outside suspension of payments or bankruptcy proceedings, it is therefore difficult to enforce a private plan with a business’s creditors. As a basic principle, a creditor can be forced to cooperate in implementing a plan offered to it only in very specific instances of abuse of rights. This is clear from the case law of the Supreme Court of the Netherlands (cf. the judgment in Mondia v. curators V&D[5], with reference to the earlier judgment in Groenmeijer v. Payroll[6]). In the Groenmeijer v. Payroll judgment, the Supreme Court held, inter alia, regarding cooperation required in interim relief proceedings in an out-of-court plan with creditors:

‘Regarding the conclusion and consequences of such a plan, the special conditions and guarantees in the Bankruptcy Act for compositions arranged under a bankruptcy, suspension of payments, and debt rescheduling scheme for natural persons, which would allow that such a plan – which, partly in view of the interests of the general body of creditors, is also subject to judicial supervision – can have binding force, including with respect to an affected creditor who does not agree to it, do not apply. In an out-of-court plan such as this one, to which the ordinary rules of the law of obligations apply, a creditor is free, in principle, to refuse the plan offered to it by the debtor – which means that it is paid only a limited part of its claim and waives its right to payment of the rest. An exception may apply if the exercise of this power is abused (Article 3:13 of the Dutch Civil Code) and the creditor could not reasonably have refused to accept the offer.’

The ACPP, which provides for a ‘court confirmed plan’, will plug this gap identified by the Supreme Court.

The same problem applies to shareholders. Existing shareholders may be asked whether they wish to make an additional investment or agree to the issue of new shares. In principle, however, the shareholders are free to decide whether or not to cooperate [7] and cannot be forced to subscribe for new shares.

The core problem, therefore, is that the Netherlands currently lacks an adequate statutory arrangement for compulsory debt restructuring (outside suspension of payments or bankruptcy proceedings)[8]. As a result, individual capital providers can frustrate and even thwart the debt restructuring process. We explain this below.

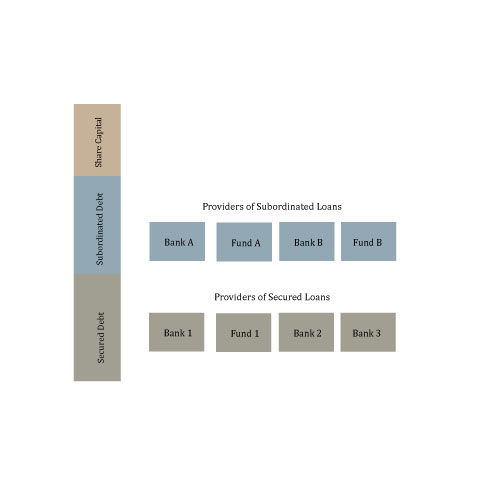

A business could have been financed by various capital providers, ranging from providers of equity to borrowed capital. These different capital providers usually have different financing conditions and collateral positions[9].

For example, the capital structure of the average business is layered; from shareholders with no security rights to creditors with security rights. Creditors may also be grouped together, such as banks or investment funds that have jointly granted loans to a business.

To illustrate this, see the image on the right, in which the subordinated loan is granted by a consortium made up of Bank A, Bank B, Investment Fund A, and Investment Fund B. The secured loan is provided by a consortium made up of Bank 1, Investment Fund 1, Bank 2 and Bank 3.

As stated above, a private plan currently requires the full cooperation of the capital providers. But why would a shareholder or a creditor with a limited or no security right of zero value participate in debt rescheduling if this would cause it to lose or weaken its position? These capital providers will try to frustrate the process under the motto: buy us out for a certain amount of money then. They will also try to gain more time in the hope of improved conditions[10].

Horizontal contrasts can also occur alongside these vertical contrasts in the capital structure. For example, most parties within a bank consortium may wish to participate in the financial restructuring, but some of them may be opposed. Since the decision within the bank consortium to suspend payments (interest payments or repayments) often requires the unanimous approval of the entire consortium, several opposing parties within the consortium may frustrate the process and realise their nuisance value. The ACPP bill provides a solution to these cases as the court can approve a plan to bind capital providers who have not agreed to it.

European Restructuring Directive

We also note that the ACPP bill is very much in line with the recently adopted European Restructuring Directive[11], which, inter alia, requires Member States to ensure that ‘where there is a likelihood of insolvency, debtors have access to a preventive restructuring framework that enables them to restructure, with a view to preventing insolvency and ensuring their viability, without prejudice to other solutions for avoiding insolvency, thereby protecting jobs and maintaining business activity.’[12] However, according to the Minister, a separate bill will be drawn up for implementing the Restructuring Directive, in which the above part of the Directive will be implemented by ‘bringing the current regulation on the suspension of payments plan into line with the Directive.’[13]

Scope and conditions for applying the ACPP

The ACPP bill contains conditions that the plan must meet before the court confirms it. We discuss the main conditions below.

1 State of inevitable insolvency

The debtor on whose behalf the plan is offered must be in a situation in which ‘it can reasonably be assumed that the debtor will not be able to continue paying its debts as they fall due’ (Articles 370(1) and 371(3) ACPP). This criterion is very similar to the criterion for applying for a suspension of payments (Article 214(1) of the Bankruptcy Act), which reads as follows: ‘The debtor who foresees that it will be unable to proceed with the payment of its due debts may apply for a suspension of payments.’ The Explanatory Memorandum refers to a situation of ‘inevitable insolvency’[14]. The plan and the information provided to those involved must substantiate the extent to which it can reasonably be assumed that insolvency is inevitable. The interpretation of this substantiation can be compared with the substantiation given in the Insolvency Opinions. We will discuss this in more detail in our follow-up article ‘Insolvency under the ACPP’.

2 Viable activities or a controlled wind-down

According to the Explanatory Memorandum[15], the plan may aim to:

(a) prevent the imminent bankruptcy of a business that has returned to financial health after restructuring (‘restructuring plan’),

(b) liquidate a business that no longer has and will not have any prospects of survival, by which a better result will be achieved than if liquidation occurs in a bankruptcy scenario (‘liquidation plan’ or ‘controlled wind-down’).

We note that objective b) is new compared to the previous preliminary draft. Partly on the recommendation of INSOLAD, this second scenario is now also possible[16].

The plan must contain all the information needed for creditors and shareholders with voting rights to come to an informed opinion on the plan before having to vote on it (Article 375(1)). The court may reject the request to confirm the plan if its performance is not adequately safeguarded (Article 384(2)(e)). If the court considers it necessary for its decision, it may decide to appoint one or more experts (Article 384(6) read in conjunction with Article 378(5)).

If there is a restructuring plan (objective a), the plan will obviously have to contain adequate information to assess the viability of the activities. However, the question is what constitutes viable activities, and what standard should be used to measure them? Is this based on relative standards, such as return on invested capital, or is it based on a cash flow approach? Are future investments included in the assessment of whether activities are profitable? How quickly must the activities become profitable? Should they be profitable immediately after the plan is implemented or should there be a prospect of profitable activities in the future?

If the reorganization (or going concern) value is lower than the liquidation value, the business has no right to exist in its present or future form. A liquidation, whether or not in the form of a controlled wind-down, is more obvious in this scenario than debt restructuring. We can then speak of a ‘liquidation plan’.

We will discuss the above in more detail in our follow-up article ‘Profitable activities under the ACPP’.

3 Approval of the plan by at least one class of creditors

The plan may amend the rights of shareholders and creditors or any number of them (Article 370(1)). The plan must therefore be submitted to the capital providers concerned for approval. However, the rights of creditors and shareholders if the debtor’s assets are liquidated in a bankruptcy scenario may be so different that there is no comparable position. The same applies to the rights offered to capital providers under the plan. It is therefore necessary to divide the capital providers into classes (Article 374 ACPP). Article 9(4) of the Restructuring Directive stipulates: ‘As a minimum, creditors of secured and unsecured claims shall be treated in separate classes for the purposes of adopting a restructuring plan.’ Voting then takes place on a class-by-class basis. Only those creditors and shareholders whose rights are amended under the plan are entitled to vote (Article 381(3)). Court confirmation can be requested only if at least one class has agreed to the plan. This must be a class consisting of creditors[17] that, in the event of the debtor’s bankruptcy, would be expected to receive a cash payment (Article 383(1)). If the plan concerns only creditors that are not expected to receive any payment in a bankruptcy, this latter requirement does not apply.

Because the plan can have different consequences for different classes, the division into classes is important. We will discuss this in more detail in our follow-up article ‘Classification under the ACPP’.

4 Pure decision-making

Because the question of whether a plan can be confirmed depends largely on the support for it, the purity of the decision-making process is very important. In view of this pure decision-making process, the bill contains several general grounds for refusal. For example, the confirmation request must be refused if:

- the debtor or the restructuring expert has not complied, or has not complied in time, with certain obligations to provide information to all creditors and shareholders with voting rights[18], unless the creditors and shareholders concerned confirm that they accept the plan (Article 384(2)(b));

- the plan or the appended documents do not contain all of the information prescribed[19], the class formation[20] or the voting procedure[21] did not comply with the statutory requirements of Article 381, unless the shortcoming could not reasonably have led to a different outcome of the vote (Article 384(2)(c));

- a creditor or the shareholder should have been admitted to the vote on the plan for a different amount, unless that decision could not reasonably have led to a different outcome of the vote (Article 384(2)(d)).

The court will deny the confirmation request if one of these general grounds for refusal applies. It can do so at the request of a creditor or shareholder with voting rights, but also of its own motion.

5 Reasonable plan

The plan must be reasonable. This means that the capital providers involved in the plan benefit, or at least are not worse off, from the plan, when it is put into effect. To test this, a comparison must be made between two situations. First, there is the expected value that can be realized if the plan is put into effect[22]. This is the ‘reorganization value’ (Article 375(1)(e)). Second, there are the expected proceeds that can be realized from liquidating the assets of the debtor in bankruptcy[23]. This is the ‘liquidation value’ (Article 375(1)(f)).

According to the Explanatory Memorandum, this can be broken down into three requirements for the plan:

- the plan must not make the capital providers worse off[24] than in bankruptcy (Article 384(3) of the ACPP). The minimum distribution for a capital provider is therefore its relative share in the liquidation value;

- the reorganization value must be distributed fairly among the capital providers (i.e. in accordance with the statutory ranking), unless one or more classes agree to a different proposal (Article 384(4)(a));

- creditors expected to receive a cash payment if the debtor is declared bankrupt should have the right to ‘opt out’ (i.e. the possibility to opt for a cash payment) (Article 384(4)(b)).

According to the Explanatory Memorandum, the grounds for refusal referred to in Article 384(3) and (4)[25] are largely inspired by two sections from the Chapter 11 procedure in the United States of America: the ‘best interest of creditors test’ and the ‘absolute priority rule’. We will discuss these in more detail in a follow-up article.

The court may[26] refuse the confirmation request on the ground referred to in point a) only if it is requested to do so by one or more creditors or shareholders with voting rights that have not consented to the plan themselves, or who have been wrongfully denied admission to the vote. This ground for refusal may also be invoked if all classes have agreed to the plan.

With regard to grounds b) and c), refusal must follow on these grounds if the relevant requirements are not met and the request in question is made by one or more creditors or shareholders with voting rights who have not consented to the plan themselves and have been placed in a class that has not consented to the plan, or who have been wrongly refused admission to the vote and should have been placed in a class that has not consented to the plan. These two grounds for refusal can be invoked only if the plan in question has not been accepted by all classes.

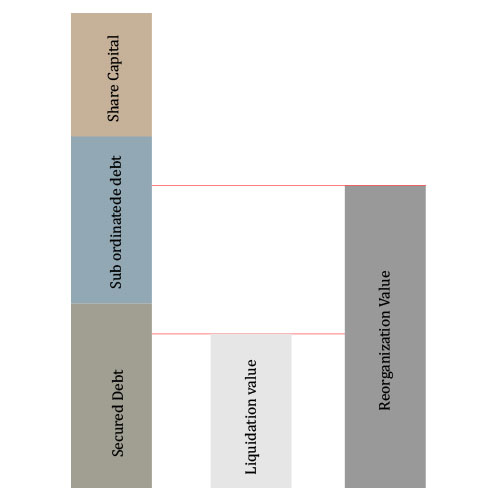

Liquidation value and reorganization value

Determining the liquidation value and the reorganization value is essential when implementing financial restructuring under the ACPP. After all, capital providers can exercise their relative claim to these two different values. A higher or lower liquidation value or reorganization value can determine whether or not a class receives a distribution or what the amount of this distribution is. After all, what matters is the size of the ‘cake’ that is distributed among the classes and whether this cake is large enough to give a certain class a distribution. So the question is where the value breaks in the capital structure. This principle is shown in the image on the right. The liquidation value is lower than the nominal value of the loans with security rights. In a liquidation scenario, only the holders of secured loans receive any proceeds. The shareholders and holders of subordinated loans receive nothing in this scenario. If the reorganization value is realized, it will be divided between the holders of secured loans and the holders of subordinated loans. The shareholders receive nothing in this scenario.

The further question is how the reorganization value is divided between the holders of the secured loans and the holders of subordinated loans. In the example, the value of the holders of secured loans clearly remains intact and the residue is distributed to the holders of the subordinated loans.

Determining the economic value of a business is not easy and the valuation principles (including the business plan in which the financial forecast is included, the capital structure, and the discount rate) can lead to much debate. We will discuss the valuation aspects that must be considered to arrive at both values in more detail in our follow-up article ‘Liquidation Value and Reorganization Value under the ACPP’.

To determine the reorganization value, there is also the question of how the new capital structure will look after the reorganization has been completed. This aspect is not only important from a valuation perspective; it is also important for amending capital providers’ rights. For example, loan conditions may change, including repayment schedules, loan maturities, interest surcharges, financial agreements, and so on, or lenders may become shareholders in the new capital structure (with all the associated rights and obligations). Under Article 375(1)(d) ACPP, the financial consequences for a class must be made clear, as part of providing information to a class, before the vote is held. We will explain the influence of the capital structure on the value of a business, and also show an example of the financial consequences of the reorganisation for a class, in our follow-up article ‘Capital structure under the ACPP’.

New capital

The bill stipulates that the plan must contain certain information. If new capital is provided, information about it must also be provided. For example, Article 375(1)(i)[27] requires information to be provided on the new financing the debtor wishes to obtain to implement the plan, and why this is needed. However, the court will refuse the confirmation request if the interests of the general body of creditors are substantially harmed by entering into this new financing.[28] We will discuss this in more detail in our follow-up article ‘New capital under the ACPP’.

Actio pauliana

The bill also contains a provision that will make it easier for a business in dire straits to obtain new financing. Under current law, the party that provides new financing to a business in dire straits runs the risk of the bankruptcy trustee annulling the plan in question if bankruptcy occurs, invoking the ‘bankruptcy pauliana’. That fate then also affects the stipulated securities. According to the Supreme Court, the actio pauliana can be invoked, if[29]:

´… at the time of the act, both the debtor and the person with or in respect of whom the debtor performed the act, could foresee the bankruptcy and a shortfall in it with a reasonable degree of probability. This criterion also applies if, as in this case, the legal act is performed as part of an attempt to avert bankruptcy through a reorganization.’

The problem in these cases is that it is not always easy to determine whether a situation as intended by the Supreme Court exists. To provide more stability and certainty in practice, the ACPP therefore contains a provision that modifies the bankruptcy pauliana. A new Article 42a of the Bankruptcy Act will read as follows:

A legal act performed after the debtor has filed a declaration with the clerk of the court as referred to in Article 370(3), or after the court has appointed a restructuring expert under Article 371, cannot be annulled by invoking the previous article, if the court has authorized that legal act at the debtor’s request. The court will comply with this request if:

a. the legal act is needed for the debtor’s business to continue during preparations for a plan as referred to in the stated articles, and

b. it can reasonably be assumed at the time authorization is granted that the legal act is in the interests of the general body of creditors and that the interests of the individual creditors are not materially affected.

According to the Explanatory Memorandum, this new article aims to promote the provision of finance for putting a plan into effect. This does not only concern financing in the form of a loan, but also, for example, supplying goods on credit. The proposed new Article derogates from Article 42 of the Bankruptcy Act. Under the latter article, voluntary legal acts that the debtor has performed prior to being declared bankrupt, and as a result of which creditors have been prejudiced, can be annulled. The new Article 42a relates to a situation where an attempt was made to put a plan into effect before the bankruptcy and financing was provided in that context. Article 42a allows the debtor to seek authorization from the court for the legal acts needed to obtain financing. The court will grant that authorization if the above two conditions have been met. The court’s authorization prevents the bankruptcy trustee from annulling the legal acts concerned under Article 42 of the Bankruptcy Act if the business is subsequently declared bankrupt. Article 42a of the Bankruptcy Act is in line with Articles 17 and 18 of the Restructuring Directive.

Amendment or termination of agreements

As mentioned, the plan can amend the rights of all categories of creditors. Reciprocal agreements can also be amended in this context. The ACPP bill makes it possible to unilaterally terminate existing agreements if the other party does not agree to a proposed voluntary amendment or termination (Article 373). For example, where a lease hangs around the business’s neck like a millstone (cf. the V&D case referred to in footnote 5). The debtor may include in the plan any (unsecured) claim for compensation to which its contracting party becomes entitled after the unilateral, premature termination of the agreement[30]. However, employment contracts cannot be amended[31]. We will deal with this topic in more detail in our follow-up article ‘Agreements under the ACPP’.

Provision of information to interested parties and the obligation to cooperate

The plan must contain all the information needed for creditors and shareholders with voting rights to come to an informed opinion on the plan before having to vote on it (Article 375(1)). The plan will be refused if the debtor or the restructuring expert has not complied, or has not complied in time, with certain obligations to provide information to all creditors and shareholders with voting rights[32] , and/or if the plan or the appended documents do not contain all of the information prescribed.[33]

However, information must also be provided after voting, in the report on the vote that the debtor must prepare after the vote, in which it states the result of the vote[34]. In addition, the debtor must ensure that the affected creditors and shareholders are immediately able to take note of the report (Article 382(1)). This is particularly important when the debtor decides to submit a request for confirmation of the plan. Indeed, the report contains information relevant for creditors or shareholders who did not accept the plan and are considering asking the court to deny the request to confirm it (Article 383(8)). The information in the report will help them make an initial assessment of the likelihood of such a request succeeding. Should they decide to actually submit a request, this information can be used to substantiate their objections to the confirmation. If the debtor submits a request for confirmation, it must file the report with the clerk of the court that will consider the request. The creditors and shareholders with voting rights will then be able to inspect the report until the court decides on the confirmation request (Article 382(2)).

In conclusion

The ACPP bill clearly takes inspiration from the British Scheme of Arrangement and the US Chapter 11 procedure. The possibility of a pre-insolvency plan, as provided for in the ACPP bill, will give businesses on the brink of insolvency a very attractive opportunity to restructure by imposing a compulsory plan on their creditors and shareholders, outside suspension of payments and bankruptcy proceedings. Businesses will need help from both legal and financial specialists to properly flesh out and implement the envisaged restructuring. With all its possibilities, the ACPP will put the Netherlands firmly on the map in the world of restructuring. Soon it will no longer be necessary, as Van Gansewinkel Groep BV did in 2015, for example, to move to England for this purpose. With the introduction of the ACPP, the Netherlands is expected to become a very appealing jurisdiction for struggling companies wishing to restructure.

===========

[1] P.C. van Prooijen RV is a partner of the financial consultancy firm Hermes Advisory, which focuses on providing financial expertise in legal disputes. He has many years of experience in the special accounts departments of large commercial banks. Pieter Christiaan is entered as a registered valuator (NIRV) in the National Register of Court Experts (LRGD), specialising in business valuations and financing. Martin Poelman is a lawyer at Wintertaling Advocaten & Notarissen in Amsterdam, and a member of INSOLAD.

[2] We will refer to the shareholders (or equity providers) and creditors jointly as capital providers below.

[3] Article 370(1).

[4] Explanatory Memorandum, no. 2.

[5] ECLI:NL:HR:2017:485; Supreme Court 24 March 2017, para. 3.4.2.

[6] ECLI:NL:HR:2005:AT7799; Supreme Court 12 August 2005.

[7] For an exception, see the Inter Acces case (ECLI:NL:HR:GHAMS:2010: BO2834, decision of the Enterprise Chamber of 3 November 2010) cited in the Explanatory Memorandum, in which the Enterprise Chamber ruled that in special cases of financial distress (emergency funding), it may grant a temporary order authorizing the management board to issue new shares to a shareholder, with the exclusion of the pre-emptive right for the other shareholders, in the absence of a general meeting resolution. That implies deviating from the provisions of Articles 2:206 and 2:206a of the Dutch Civil Code. The Supreme Court rejected the appeal in cassation against this judgment (ECLI:NL:HR:2011:BO7067, Supreme Court 25 February 2011).

[8] Explanatory Memorandum ACPP page 1.

[9] Besides the collateral position (also pay attention here to structural subordination), it is important to consider the chronological order in which creditors will be repaid (for example, a secured creditor may be in a worse position than an unsecured creditor who is repaid earlier).

[10] This situation is compared to extending the expiration date of an out-of-the-money call option. If the option is exercised now, it will be worthless. If the expiration date is extended, it could become in the money and thus still have some form of value. The probability that it will go into the money represents an ‘option value’.

[11] In full, it is Directive (EU) 2019/1023 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on preventive restructuring frameworks, on discharge of debt and disqualifications, and on measures to increase the efficiency of procedures concerning restructuring, insolvency and discharge of debt, and amending Directive (EU) 2017/1132. The short title is: Directive on restructuring and insolvency.

[12] Article 4(1) of the Restructuring Directive.

[13] According to Minister Dekker’s Progress Letter on the Bankruptcy Law Review Programme of 27 August 2019.

[14] See the Explanatory Memorandum on Article 371(4), page 45.

[15] Explanatory Memorandum no. 3 on page 5.

[16] Explanatory Memorandum no. 4 on page 26.

[17] This read differently in an earlier draft. According to Article 380(1) of the preliminary draft, a class sufficed.

[18] First, this concerns the obligation under Article 381(1) (‘The debtor or the restructuring expert as meant in Article 371, if appointed, shall make the plan available to creditors and shareholders with voting rights for a reasonable period of at least eight days before the vote, or inform them how it can be accessed, in order that they can come to an informed opinion.’). Article 383(4) further stipulates that the court shall issue a decision scheduling a hearing to consider the confirmation. The debtor or the restructuring expert must promptly send written notice of the decision to creditors and shareholders with voting rights (Article 383(5)).

[19] In this context, Article 375 stipulates:

1. The plan shall contain all information that creditors and shareholders with voting rights need to come to an informed opinion prior to the vote as meant in Article 381, including:

a. the name of the debtor;

b. the name of the restructuring expert, where applicable;

c. the class formation and the criteria used to place creditors and shareholders in one or more classes, where applicable;

d. the financial consequences of the plan for each class of creditors and shareholders;

e. the expected value that can be realized if the plan is put into effect;

f. the expected proceeds that can be realized from a liquidation of the assets of the debtor in bankruptcy;

g. the principles and assumptions used in calculating the values referred to in (e) and (f);

h. where the plan involves the allocation of rights to creditors and shareholders: the moment or moments at which the rights are allocated;

i. the new financing the debtor wishes to obtain to implement the plan, where applicable, and why it is needed;

j. the manner in which creditors and shareholders can obtain further information on the plan;

k. the procedure for voting on the plan and the time of the vote or the deadline for casting votes; and

l. the manner in which the works council or workplace representation that is set up in the debtor’s business in accordance with Article 25 of the Works Councils Act has been or will be asked to issue its advice, where applicable.

2. The following shall be appended to the plan:

a. a properly documented statement of all assets and liabilities;

b. a list containing:

1. the identity of the creditors and shareholders with voting rights by reference to name or, if that is not possible, by reference to one or more categories;

2. the amount of their claim or the nominal amount of their share; and

3. a specification of the class or classes into which they have been placed.

c. where applicable, the identity of the creditors and shareholders that are not included in the plan by reference to name or, if that is not possible, by reference to one or more categories, together with an explanation of why they are not included in the plan;

d. information on the financial position of the debtor; and

e. a description of:

1. the nature, extent, and cause of the financial problems;

2. what attempts have been made to solve these problems;

3. the restructuring measures that are part of the plan;

4. how these measures contribute to a solution; and

5. how long implementation of these measures is expected to take.

3. An order in council may stipulate what other information must be included in the plan or the appended documents, how that information is to be supplied, and may also provide a form template.

[20] In this context, Article 374 stipulates the following:

Creditors and shareholders are placed in different classes if the rights they have in liquidating the debtor’s assets in bankruptcy or the rights they are offered under the plan are so different that they are not in a comparable position. In any event, creditors or shareholders shall be placed in different classes if upon enforcement against the debtor’s assets they have a different ranking under Book 3, Title 10 of the Dutch Civil Code, any other law or instrument based on it or under an agreement.

[21] Article 381.

[22] To avoid any misunderstanding, this concerns the value for contributing possible new money (or the pre-money valuation).

[23] This expected payment does not concern only the execution value of the business’s assets (piecemeal), but can also concern the forced-sale value of the business (forced liquidation value) or a combination of the two.

[24] The Explanatory Memorandum erroneously states that the creditors and shareholders must not be ‘significantly worse off’ under the plan than in bankruptcy. The word ‘significantly’ does not appear in Article 384(3) (it appears in Article 381(3)(d) of the preliminary draft).

[25] Explanatory Memorandum pages 19 and 73-74.

[26] The word ‘may’ means that the court has a margin of discretion here.

[27] See footnote 18.

[28] Article 384(2)(f).

[29] HR 7 April 2017, NJ 2017, 177(Jongepier q.q./Drieakker), para. 3.3.2, with reference to HR 22 December 2009, ECLI:NL:HR:2009:BI8493, NJ 2010/273, ABN AMRO/Van Dooren q.q. III, para. 3.7-3.10.

[30] Article 373(2).

[31] Article 369(4).

[32] See footnote 17.

[33] See footnote 18.

[34] Explanatory Memorandum page 16.